Alison, thank you for taking the time to join us for this interview. We’re excited to learn more about your artistic journey, inspirations, and the creative process behind your sculptures. Let’s dive in!

Your artistic journey began early, with creative projects like making a cardboard house for your sister’s troll doll. Looking back, do you see a connection between those childhood experiments and the mixed-media sculptures you create today?

Absolutely. Decades ago, while trying to figure out how to create a work life in sync with our natural inclinations and skills, a good friend and I did some exercises from the book Wishcraft: How to Get What you Really Want by Barbara Sher. For one of the exercises we each described a project we did well and loved doing, and I wrote about making that furnished and decorated cardboard house for my sister’s troll. At the time, it never occurred to me I could be a mixed-media artist; I hadn’t taken a single art class in college. But years later when I made my first mixed-media project, I told that friend I had finally unleashed the part of myself that created the childhood troll house.

That early spark stayed alive. Yet you stepped away from art for many years in environmental planning and communication. What was the turning point that brought you back to creating?

I can tell you exactly when that was. After my husband and I moved from Seattle to California, I joined a group of women reading The Artist’s Way: A Spiritual Path to Higher Creativity by Julia Cameron. I created a collage (as suggested in the book); I really liked how it came out and decided to frame it and hang it in my office. Whenever I looked at it, my artistic side was reflected back to me, prompting me to sign up for an art class at the local community college. That led to other art classes and the freeing of my inner artist.

That collage marked the start of your artistic reawakening. But it wasn’t just about art—it was part of a deeper spiritual journey. How has your experience with Sheng Zhen Meditation and other spiritual practices influenced your creative process?

I believe that creativity is one quality of our true nature. Just as spiritual practices can nourish creativity, creative expression can help align us with the creativity inherent in life. But the nature of our true nature is beyond anything words can describe. I’ve tasted/sensed many flavors of it: profound stillness, a silent awareness, a flow of love, a luminosity. Exploring the nature of our nature—which I believe is the nature of all life at its most essential level—is endlessly fascinating to me.

Spiritual exploration is primarily about going inward, though the inward direction expands to the infinite. Many of my pieces have been about the inner journey. For example, the butterfly drawn to the flower in Nectar (photo below) represents the pull of the spiritual seeker toward the inner light, the inner honey-like nectar.

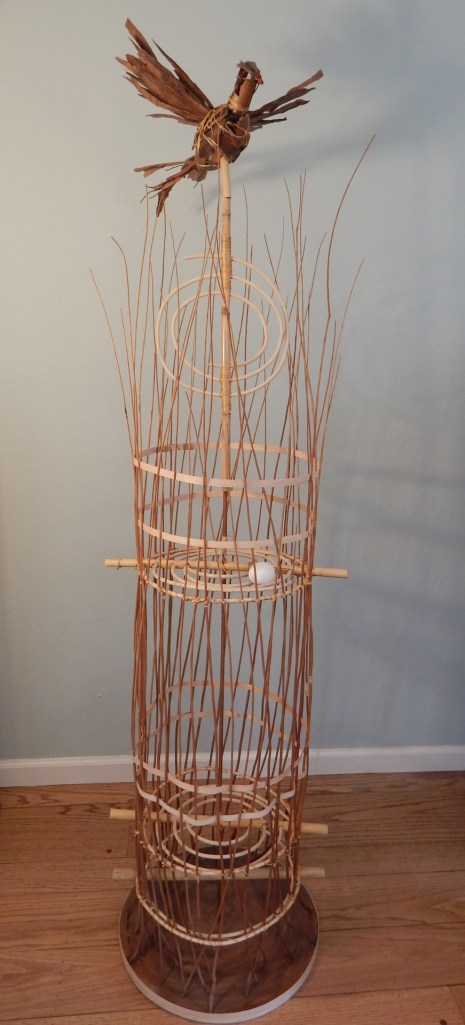

That sense of inner exploration flows through your work. In Flying the Coop, the theme expands outward into a striking vision of liberation. What was your inspiration, and how does it speak to freedom or transition?

I’ve always been fascinating by birds, which definitely symbolize freedom to me. But I didn’t have a clear vision for Flying the Coop when I began it. The piece I submitted is an iteration of a piece that began in an Introduction to 3-D design class. We were charged with creating volume out of line. If I recall correctly, everyone else in class worked with wire. I wanted to work with natural material and came across a bundle of willow branches at a caning store in a nearby town. It was love at first sight. I bought the branches without any idea of what to do with them.

Since willow branches are only somewhat flexible, I had to figure out how to create volume. I came up with a process to create what turned out to be basically a cylinder with a spiral inside it for interest. I wasn’t even done with that, so I brought the piece home to finish it before the due date the following week. When I finished my original idea, I looked at it and saw that although I had created volume out of line (the assignment) and the piece had a certain personality, I wasn’t really satisfied with it.

I studied the piece, and the wisps of the willow branches at the top reminded me of a salt marsh or meadow, and I had this ah hah moment that the piece needed a bird flying away from it. Luckily the center support for my cylinder of willow branches was a piece of bamboo, which provided the perfect pocket for inserting a support for a bird.

I had noticed bark shred from Eucalyptus trees in a nearby park, and it occurred to me the bark pieces would make great feathers for a bird. I also needed something flexible to form the bird’s body, so that’s where the wire came it. I spent the whole weekend in my office—which doubles as my art space—surrounded by wire and bark and artificial sinew and managed to create the bird.

Once the bird was perched atop, it looked like it was flying from a nest so I had the idea of adding eggs (with the egg white and yolk blown out through small holes). When I brought it to class, my teacher was amazed.

But I moved that piece one too many times and it started to come apart. I created Flying the Coop II, after learning from my construction mistakes the first time around.

It’s funny though. I always thought of the piece as symbolizing freedom, yet it struck me recently that the bird is still tethered to the nest. Perhaps that is the ongoing tension between home and adventure, between belonging and freedom.

From willow branches to eucalyptus bark, your process shows a deep sensitivity to material. How do you decide which elements to use, and what role does symbolism play in those choices?

Sometimes the choice of a material is purely practical. For example, as mentioned above, I included wire in Flying the Coop for its flexibility. Similarly, I incorporated wire into Time for the Phoenix for the support and flexibility it provides.

Sometimes the choice of material is symbolic. For example, when I created a cast torso in an art class (photo below), I wanted the piece to symbolize the inner journey and cut an opening over the heart center. I covered that opening with a piece of lace crocheted by my grandmother, symbolic of my ancestors. While peeling an onion for dinner I noticed how beautiful the outer peel is and decided onion peels would be the perfect cover for the torso, since the inner journey is likened to peeling the layers of an onion. I incorporated a small light to illuminate the interior, indicative of the inner light we each carry.

I’ve always been drawn to natural materials. I sometimes collect sticks, rocks, seed pods or other natural items I encounter on walks, solely because they strike me as beautiful.

My house is full of natural items I’ve collected, such as this collection on my computer desk, one in front of my printer, and one on a table next to my computer desk.

To me, there’s something almost magical about natural objects, and I consider Mother Nature to be the master artist. I love using natural materials in my pieces when that is practical.

Your love for natural and symbolic materials clearly shapes your art. In Time for the Phoenix, the imagery of rebirth stands out powerfully. What personal or artistic resonance does this piece have for you?

The idea to create a phoenix came from a conversation with a friend who had lost her home and all its contents (including her life’s work) in one of California’s terrible wildfires. She had designed that home, and she and her husband had literally built it themselves. But my friend was determined not to be defeated by her profound loss. The image of the Phoenix took root in my mind and wanted expression.

When I painted the paper used for the feathers, I kept thinking of fire but was focused on the beauty of the colors as well as on transformation. The dynamism of the wings was very intentional—I wanted to convey the sense of lift-off (and uplift).

The story behind Time for the Phoenix is deeply moving. Across your body of work, there’s also a sense of timelessness and the recurring presence of birds. Do these themes come from cultural traditions, mythology, or a personal symbolism of your own?

Time for the Phoenix was definitely inspired by mythology, but not the other pieces. But I love that you see an almost ancient quality to them, as though relics from another time. When I create a piece I feel I am pouring something of my own soul into it, and that the piece itself takes on its own energy or spirit that I listen to while deciding what else it needs.

Perhaps that is what you are sensing when you see them as almost ancient, because I think many, if not all, ancient cultures revered nature, approached life in a much more sacred way than we do in our fast-paced world, and perhaps imbued objects with specific qualities.

Life is deeply mysterious to me, and I have definitely experienced physical objects that have taken on energetic qualities. For example, I could feel the silence in the walls of a retreat center I used to go to for meditation retreats—it was as though the silence of the retreats got woven into the fabric of the building. Or when I visited the Spirit of the West exhibit at the Blackhawk Museum (in Danville, California), I could feel a shamanic power in many of the Native American artifacts.

Somehow, the intentions with which something is created affect the results. Two objects can look basically the same, and yet feel very different on a subtle level. My goal is to create art that resonates with the viewer on the level of the soul.

Birds are amazing creatures to me and symbolize freedom. That symbolism is probably universal, since birds live in a whole other realm. In modern life, we all have so many demands and constraints that I suspect the quest for freedom is a core inner drive.

Your reflections on energy, intention, and the universal symbolism of birds reveal how deeply your work connects with nature and spirit. Given your background in environmental planning, do you see your art as a commentary on our relationship with nature, and how does that background shape your approach?

I think the same impulses and values that led me to environmental planning also influence my art (rather than environmental planning influencing my art). Environmental values were baked into me growing up; my mother was an avid organic gardener and environmentalist and later served on our town’s Conservation Commission. I also was fortunate enough to live in a house with a stream and woods beyond our back yard, and that was my childhood playground. When I was a teenager, Ian McHarg’s seminal book Design with Nature (about integrating ecological principles in urban planning) was on our coffee table; I inevitably read it, and it deeply influenced me.

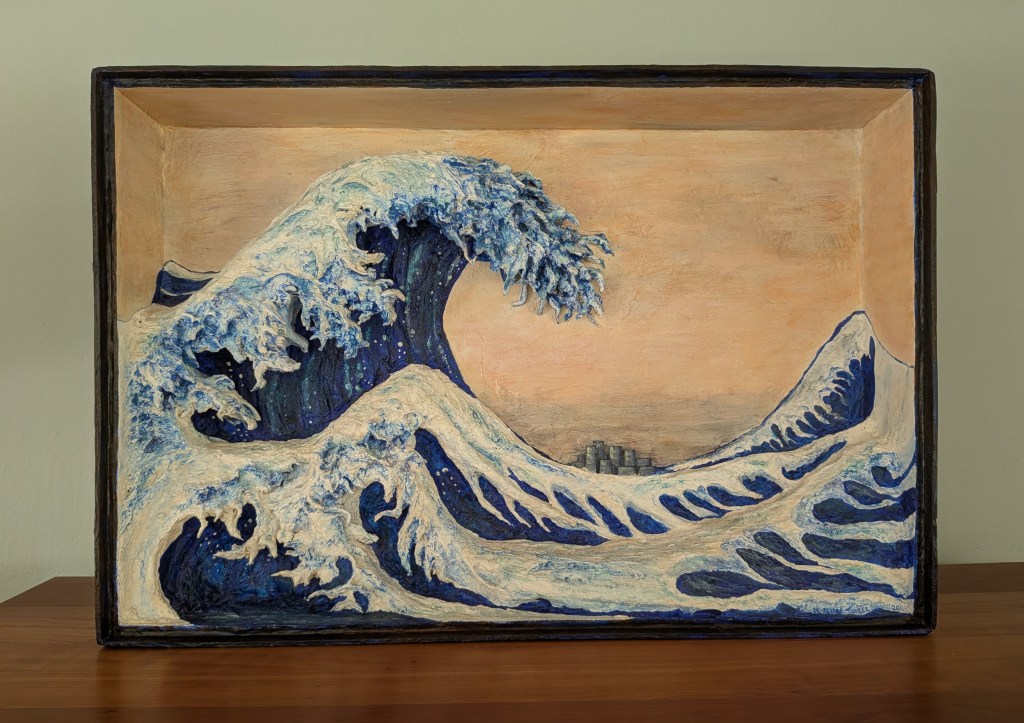

One of the pieces I created, Homage to Hokusai and the People of Japan, was in direct response to the environmental crisis. I started that piece shortly after the terrible tsunami in Japan, but it also speaks to rising sea levels and increased flooding around the globe.

Here is a photo of that piece, which I consider a work in (stalled) progress. A local artist in a critique group I was in suggested making the colors more painterly instead of like Hokusai’s print; I haven’t gotten very far doing that. Once I decide the piece is definitely finished, I plan to cover the front with plexiglass, to be held in by a frame that matches the box I constructed.

The title of my bird Propelled by Nature is itself an environmental statement. We’re all propelled by nature, as elaborated in a poem I wrote by the same name. (The poem is included at the end of this talk.)

Your art clearly carries both environmental values and personal resonance. Along this journey, you’ve also shared your work publicly. How did receiving honorable mentions in two exhibitions shape your confidence and perspective as an artist?

The first time I received an honorable mention was at the gallery for the community college where I was taking an art class. Getting that award made me look at my piece with fresh eyes and really appreciate its playfulness. I suddenly noticed how the way I had used the wire (with all the kinetic motion built into the twists and turns) was really suited to the content; I had made a large kitchen beater, called Beat It, for an assignment to make an object out of wire at a scale other than its usual one. The beater now hangs in our kitchen, and the handle actually turns, but it’s not the kind of piece I’d be inspired to make again.

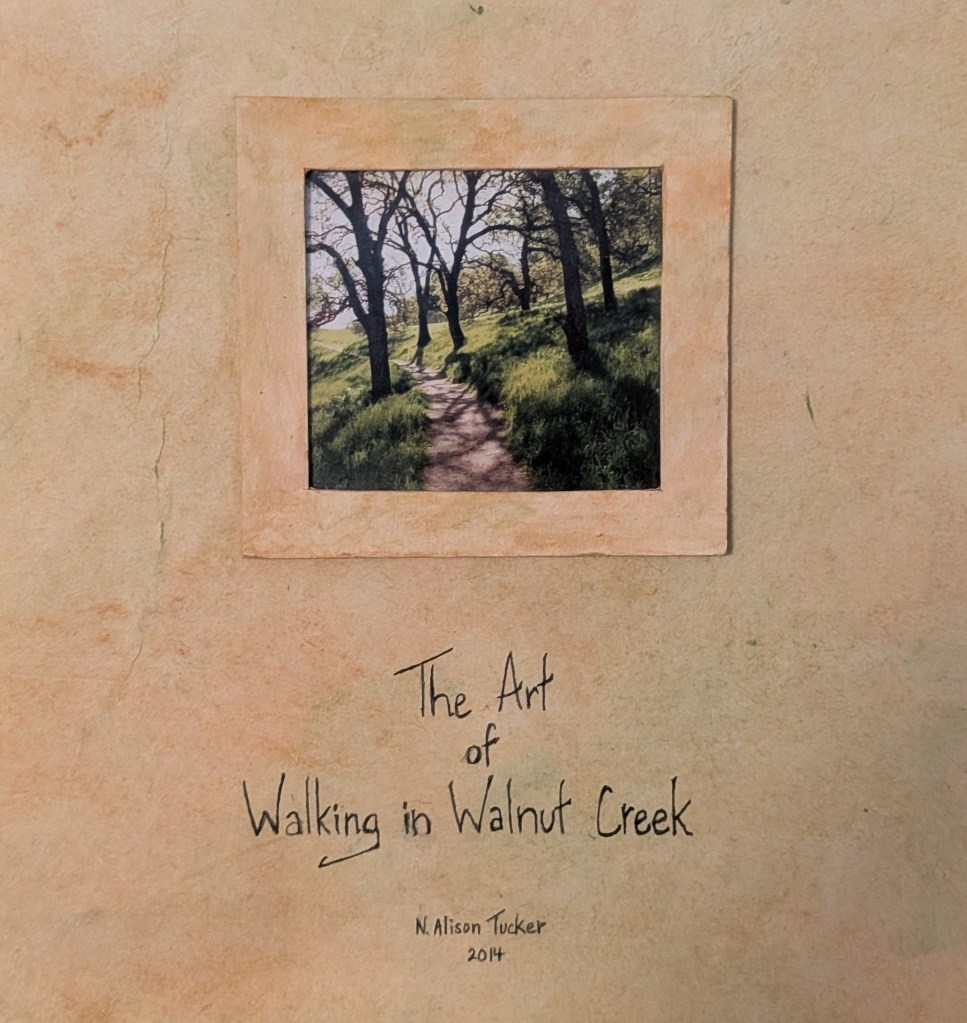

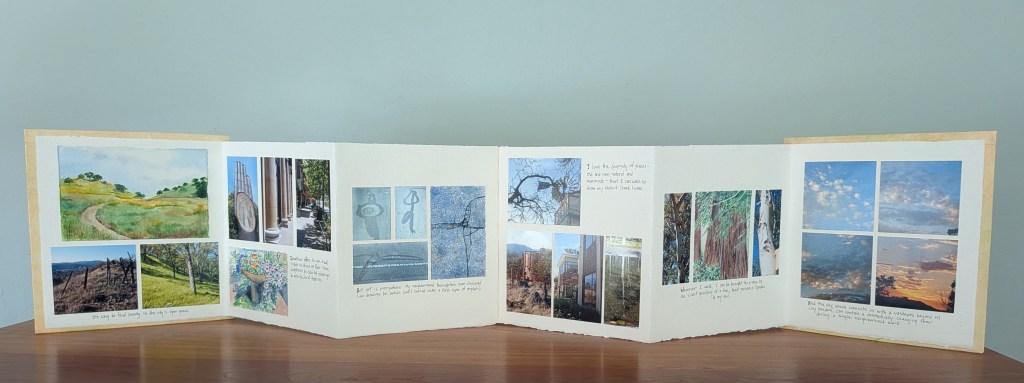

The second time was at an exhibit celebrating the city where I live in California. I created an accordion book entitled The Art of Walking in Walnut Creek with photos and watercolors of the beauty I encountered within walking distance of my home.

I appreciated the honorable mention as another acknowledgment of my artistic side.

Those early recognitions clearly affirmed your creative path and gave you fresh perspective on your work. Today, the landscape of sharing art has shifted online. How do you navigate that digital space, and how have platforms like Biafarin, Exhibizone, and Gallerium supported you?

So far I haven’t navigated the challenges of getting my work seen other than in a couple of non-juried local exhibitions. I am really terrible about social media. I created a Facebook account years ago, but basically never use it, and I haven’t created an Instagram account, website, or anything else. I’ve always been fairly introverted and there is something about the “look at me” competition of the social media world that just hasn’t appealed to me.

I have tried to get a few of my pieces in local juried exhibits, but so far haven’t been successful. Among other things, those applications asked for the artists’ resumes/curriculum vitae, which puts unknown artist at a complete disadvantage. I created the three birds that I submitted in time for a local juried exhibit entitled Bird, Nest, Nature. I thought I nailed the idea of the exhibit (and had poured my heart and soul into my creations), so I was particularly let down that none of them were accepted.

After that, I didn’t try to get an audience for any of my art until the Review Me application caught my eye. I really appreciate that Biafarin is interested in providing exposure to unknown artists, and that my birds finally have a chance to be seen. Having my work received is definitely an encouragement to keep creating.

It’s inspiring how you’ve stayed true to yourself while finding platforms that genuinely support your vision and voice. Looking ahead, what’s next for you—are there new projects or directions you’re excited to explore?

Lately, my creative energy has been focused on how to re-landscape our backyard. We had to remove a dying tree which necessitated removing a deck and led to the need for a completely new vision for our yard. I want it to be an artful, soulful place that is attractive to birds and beneficial insects while conserving water and being mindful of fire risk.

In the back of my mind, some other art projects are also percolating. But I feel it would be premature to talk about them (like pulling up a tiny plant to see if it is growing roots). Also, my spiritual practices are an ongoing commitment, including teaching Sheng Zhen Meditation.

To explore more of N. Alison Tucker’s soulful mixed-media sculptures, visit her Biafarin artist profile. Each piece resonates with spiritual depth and a reverence for nature, often taking flight through her recurring bird motifs—symbols of freedom, transformation, and the mysteries of life.

Read the “Propelled by Nature” poem here

Propelled by Nature

Amidst the vast mystery we call the Universe,

Our tiny Earth glides around a star, our Sun,

While alternately turning towards then away.

When Earth faces her star,

Sequoia, wild rose, the entire green kingdom

Seizes the gift of light and

Transforms water and carbon dioxide

Into molecules that fuel all of life.

Oxygen released in the process is

Breathed in by you, me, our four-legged kin.

We, in turn, breathe out what plants take in.

Water flows from clouds

To land and rivers and oceans and back again,

Passing through Cedar tree, buffalo, you,

Not in some incidental detour

But in a passage vital to

The living of life.

Flow and transformation

A ceaseless giving,

A constant cycling

In the weaving of the web of life.

Eagle riding the wind

Morning glory unfurling her petals to the sun

Subterranean networks of fungus and roots,

A child walking to school.

One interwoven world

In a dance

Propelled by nature.

Leave a comment